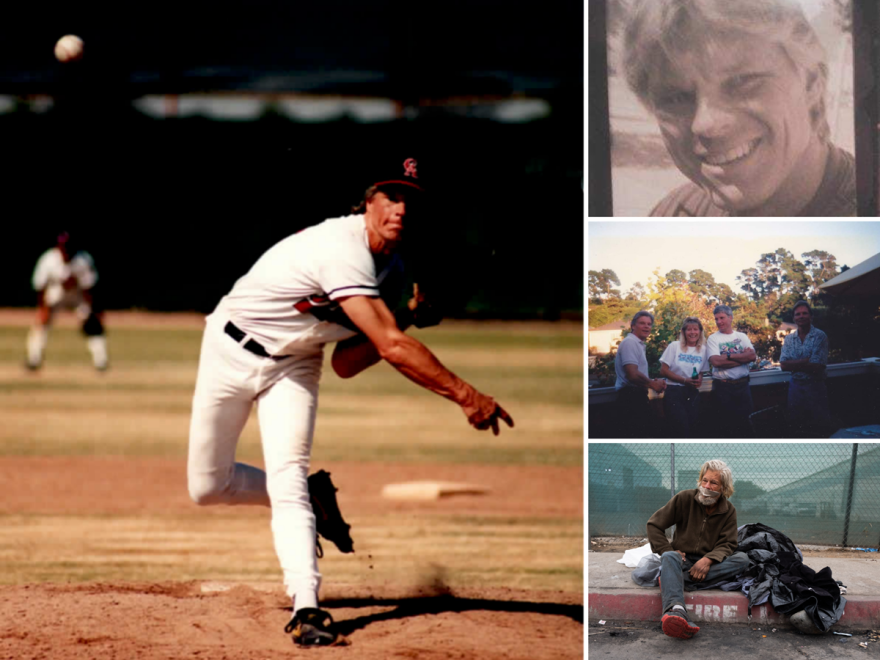

Growing up in affluent Pacific Grove on the Monterey Peninsula, Greg Tarola seemed to have it all: good looks, fast cars and lots of friends.

“Greg was a total jock, standout athlete, the whole nine yards,” said Debby Beck, who says she dated Tarola in the late 1970s, a few years after they graduated from Pacific Grove High School.

On the surface, life was good. Tarola was charismatic, kind, loved to laugh, was proud of his Italian heritage and became a skilled dental lab technician, according to interviews with friends and family.

But by his early 20s, life for Tarola got more difficult. That’s when the seizures started. He was diagnosed with epilepsy, a neurological disorder that causes uncontrollable tremors and can lead to periods of unusual behavior and loss of awareness.

As new struggles mounted, the seizure disorder stayed with him through his last days on the streets of Sacramento. On Nov. 20, Tarola was found dead, wrapped in blankets wet from the previous night’s rain, according to a from Loaves & Fishes, a nearby homeless service center.

The gregarious man from Pacific Grove was 63.

Though it wasn’t easy, Tarola managed his epilepsy successfully for decades. During that time, he got married, had two sons, worked in the software industry and even played in fast-pitch baseball leagues well into his 40s.

Still, the seizures remained a constant cloud, robbing Tarola of normalcy and pride, Beck said. Surgery and treatment failed to stop the disease, which when combined with Tarola’s financial and marital struggles later in life, quite possibly “consumed him,” she added.

Tarola spoke about his failing health with CapRadio last month near Loaves & Fishes on a chilly Sacramento morning, for a story about warming centers. The conversation took place just three days before he passed.

“I’m an older epileptic, obviously,” Tarola said, seated on a curb, hours before a rainstorm, his hands covered in dirt, and his hair long and grey.

“I lived it. I faced it,” Tarola continued, sharing that he was also diabetic and that “medication doesn’t work.”

Tarola’s photograph and his comments were featured in a CapRadio on Nov. 17. He said he had recently become unhoused.

He wasn’t alone.

Like most of California, Sacramento has struggled to solve its homelessness crisis, despite years of frustration and big-money solutions. Encampments line sidewalks and freeway overpasses, shelters are crowded and the problem shows little to no visible improvement.

But new plans in the city to build permanent housing and open warming centers during the winter for the thousands of unhoused residents in Sacramento could help to prevent deaths like Tarola’s.

Many of Tarola’s high school classmates, friends and family members have since contacted CapRadio to express both sadness and a desire to tell a fuller story about the charming and ultimately troubled man they knew decades ago.

“To my dear friend Greg I’m sorry you passed this way,” Patricia Dempsey, who went to high school with Tarola, wrote in an email. “You were worth more to life than to die cold on a sidewalk.”

Though hundreds of Californians die each year while experiencing homelessness, most do so with little notice after living largely an invisible life on the streets.

Greg Tarola’s case was an exception.

Advocates call Tarola's death avoidable

Loaves & Fishes described Tarola as “the first cold weather casualty” of the fall, with advocates saying he likely froze to death.

It was 37 degrees on the morning he was found.

As of early December, the Sacramento County Coroner’s Office listed Tarola’s cause of death as “undetermined.” A representative for the office said a full report won’t be available for several months.

Just days before his death, Tarola told CapRadio that he didn’t know warming centers existed.

That could be because Sacramento hasn’t opened one in four years.

Cities in the region usually open the sparse facilities after three consecutive nights of freezing temperatures (32 degrees or colder), based on from Sacramento County. The centers offer water, snacks and a place to escape the cold for a few hours, but are by no means full-service shelters.

Open beds at traditional shelters are nearly nonexistent, according to those who work with people who are unhoused in Sacramento. Some of the already limited supply of beds disappeared when some shelters closed at the start of the pandemic due to a lack of staffing and health concerns. Those that stayed open had to reduce capacity to comply with physical distancing rules.

When something like [Tarola's death] happens, it’s so frustrating because, to me, this is not a natural end to a person’s life. This was an avoidable end.– Joe Smith, advocacy director at Loaves & Fishes

Advocates say the criteria for opening warming centers is far too strict. For years, they’ve called for government leaders to ease the rules, pointing out that cities have the authority to open the facilities when they see fit.

“It’s unacceptable that the city and county have not opened up warming centers yet. Absolutely unacceptable,” said Bob Erlenbusch, executive director of the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness. “And Mr. Tarola’s death underscores that.”

An annual by the regional coalition showed that 138 homeless people died in 2019 in Sacramento County, or one person approximately every two and a half days. That figure was up from 132 deaths in 2018.

The report says four individuals died of hypothermia in 2019, up from one person the year before.

Joe Smith, advocacy director at Loaves & Fishes, said those deaths are much more than just a statistic, and each one is “someone’s brother or sister, someone’s child.”

“When something like [Tarola’s death] happens, it’s so frustrating because, to me, this is not a natural end to a person’s life,” added Smith, who spent five and a half years unhoused. “This was an avoidable end. Who knows what he could have done? Who knows whose life he could have impacted?”

Last week, change seemed to be on the way.

Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg during the City Council meeting. He said it was “the humane thing to do,” regardless of whether the criteria was met.

Warming centers cost $1,900 to operate for 12 hours and are typically located inside city-owned facilities, such as community centers.

Local officials say few people take advantage of them, though advocates argue that’s because it’s difficult for unhoused people to get to them. Advocates also say more needs to be done to inform people on the streets out about the centers.

“We have to do this,” added Steinberg, who co-chairs Gov. Gavin Newsom’s statewide homelessness task force. “We ought to do it, and we will do it, I hope, in collaboration with our county partners.”

But despite the mayor’s call, the centers stayed shut.

Instead, City Manager Howard Chan said he would continue conversations with the county about how to safely open the facilities amid the worsening COVID-19 crisis.

“We cannot open small centers, for example, because of the spacing and distancing requirements,” the mayor explained last week on . “We have to look at facilities like our libraries and see if that is a fit.”

There’s no mention of further discussions about the centers on this week’s meeting agendas for City Council or Board of Supervisors.

One part of a larger strategy

Warming centers are just one small piece of Sacramento’s strategy to fight homelessness.

Steinberg to create a master plan to find locations to build homeless shelters. The plan would bypass the neighborhood opposition that often kills the construction of homeless shelters and camping sites.

Earlier this year, the city and county helped move approximately 1,100 unhoused people into hotel and motel rooms through the state’s Project Roomkey, according to Mary Lynne Vellinga, the mayor’s spokesperson. That program used federal money to ensure shelter for Sacramento’s most vulnerable during the pandemic.

With the federal money set to expire at the end of December, Sacramento is now taking part in the state’s next initiative, Project Homekey, to buy motels and create permanent homeless housing.

But advocates fear the permanent space might not be ready in time.

“Those hotels are beginning to close,” Erlenbusch said of the rooms being funded through Project Roomkey. “We will put out hundreds of homeless people at the height of the holiday season.”

It’s not clear how many people have been, or will be, displaced when the project ends.

There were nearly 5,600 people experiencing homelessness in Sacramento County in 2019, according to the . Statewide, there were more than , the most in the nation, according to a recent federal report.

It is just so inhumane. We can so easily fix it.– Sacramento City Councilmember-elect Katie Valenzuela

Nearly 72% of California’s homeless population was unsheltered, living on the streets, in a vehicle or an abandoned building.

Sacramento City Councilmember-elect Katie Valenzuela said the city’s homelessness crisis — including the debate over warming centers — is one of the reasons she decided to run for public office.

“It is just so inhumane,” Valenzuela said of keeping the centers closed, adding that the city can afford to pay the $1,900 cost to open them for a night. “We can so easily fix it.”

“We can figure out a way to finance stadiums, to finance convention centers. Anytime we want to do something, we find a way to pay for it,” she continued. “But for some reason, saving a life, or multiple lives as we’re likely to see this winter, just doesn’t raise to that level of priority.”

'The good parts of Greg were really good.'

Natalie Lane met Greg Tarola in the early 1990s through coworkers who played softball with him in the Bay Area. The two hit it off, were married in 1995 and had a son, Christopher, who is now 23. They lived in Pleasanton, a suburb in Alameda County.

Lane described Tarola as charismatic, good with computers and a huge sports fan. “The good parts of Greg were really good,” she said.

That included his lifelong passion for baseball, which led to coaching stints at his high school alma mater.

“Greg coached baseball off and on at Pacific Grove and was a terrific help to me as a head coach, and as a player before that,” Jeff Gray, the high school’s football coach and former baseball coach, wrote in a about Tarola.

“He always had something positive to say,” Gray added.

Tarola also played in a 40-and-over fastpitch baseball league and would travel to Arizona each year with Lane and his team to take part in a World Series tournament.

Lane said Tarola took medication to keep his epilepsy under control throughout their five-year marriage. The disorder was present but didn’t dominate his life.

The bigger challenge, she said, was the pressure he felt to be the perfect “cookie-cutter family.”

“He wanted to be a family really, really bad,” Lane added.

But ultimately, Tarola’s struggles with responsibility, drinking and his “demons,” were too much, she continued.

“He just couldn’t do it,” she said.

After Tarola lost his job, Lane said the couple experienced financial troubles, then stress and heated arguments.

“There was lot of marital challenges because of the finances,” Lane explained. “Our marriage just couldn’t … I couldn’t sustain it.”

The couple divorced. Tarola found temporary jobs and relationships, moving to several cities including Lodi and eventually Sacramento.

“He just couldn’t find anything solid for himself,” Lane said. “He bounced around in jobs, he bounced around girlfriends, he bounced around residences. He kept trying but he couldn’t get that leg up.”

Tarola also kept trying to beat the neurological disorder that dogged much of his life: epilepsy. Less than a decade ago, he underwent surgery and treatment to fight it. The effort largely failed, according to family and friends.

“I’ve had the surgery in 2012 at Stanford,” Tarola offered in the short interview with CapRadio in November. “People get to know me and then find out who I am. They don’t like being close to an epileptic, that’s for sure.”

Tarola also shared that he had tested positive for COVID-19 a few days before speaking with CapRadio. Because of the positive test and his medical history, Tarola would have been at the top of the list for emergency homeless housing under state guidelines.

It’s unknown whether he was offered such shelter, and if he was, whether he rejected it.

Sacramento County health officials conduct monthly COVID-19 testing near Loaves & Fishes. Kim Nava, a county spokesperson, said she could not confirm a person’s health information citing privacy laws. She said, however, that all who test positive are offered and encouraged to accept shelter services at medical isolation units for people experiencing homelessness.

Nava added that COVID-19 tests are also conducted on all bodies brought to the coroner’s office, and that no one suspected of being unhoused had tested positive in November.

Despite Tarola’s misfortunes, Lane said her ex-husband wasn’t blameless — family and friends reached out and repeatedly offered help.

Had Greg been given a shower and a warm place to sleep, I don’t think he would have died.– Natalie Lane, Greg Tarola's ex-wife

Lane said she has thought a lot about homelessness; her father was a police officer who ended up on the streets late in his life, as well. At one point, Lane said she purchased her father a car so he’d have shelter, then eventually helped him gain admission to a nursing home through a veteran’s program.

“You can’t save them,” she said. “You can’t fix all their problems.”

Still, she said she believes communities can take some basic steps such as providing shelter at night. “I definitely think that there is an opportunity for just a little more human compassion,” Lane added.

“Had Greg been given a shower and a warm place to sleep, I don’t think he would have died,” she said. “I think he died in the elements and I’m still waiting to find out if that’s true, but I think he died of hypothermia.”

“And that’s just not right,” Lane said, as she wept. “It’s just not right.”

Copyright 2020 CapRadio