Sara Harper says nothing really prepares you for the moment you put on that 911 headset.

"There's a little spike of adrenaline because you're like, 'oh, god, here we go,'" says Harper, who started at Denver 911 in 2013. "'What is this going to be? Is it just going to be an easy one? Is this going to be an annoying one? Is this going to be the call that changes my life?'"

For decades, 911 call takers have had three main options: send emergency medical responders, fire and police. A fourth option is becoming increasingly common: a mental health professional who responds to some calls instead of police. A found that 44 of the largest U.S. 50 cities now have an alternative response program, many of which don't involve police at all.

As more cities deploy these new responders, the decision of when to use them usually rests with already stressed 911 workers.

Harper found her job as a 911 call taker very rewarding. She felt like she was really helping people. But she often worked long hours and struggled with anxiety. After a few years, she decided it was in her best interest to put the headset down.

That experience isn't unusual, says Jessica Gillooly, an assistant professor of sociology and criminal justice at Suffolk University.

"Nationally, I'd say that right now it's not a great time in the 911 call taking system. Some might say it's in crisis itself," Gillooly says. "Workers are overstressed, they're understaffed and they're underpaid."

In a last year, more than 80 percent of respondents said their facility was understaffed. Almost the same amount said they regularly deal with burnout and anxiety.

"You are the voice amidst the chaos, but you're not seen. And because you are not on scene, you're not uniformed, you're not interacting with someone at the location, you're forgotten about," says Carlena Orosco, an assistant professor of criminal justice at California State University, Los Angeles, who spent nine years as a dispatcher.

"You're considered someone who gets resources, handles things, gets officers to the scene, and then you're kind of left out of the picture at that point," she added, "without having any closure or resolution or even being treated as though you're a key decision maker, which you are."

'We have to make sure that people are on the same page'

Deciding what might be a good fit for an alternative response can be challenging, Gillooly says.

"It can be hard to understand what's going on in the moment. The information can be incomplete," she says. "Call takers are trying to figure out, is this a call that we can divert to an alternative responder or not? Their decision right there is really going to shape the trajectory of that call."

The stakes are high.

"You immediately have to just figure out how to handle the situation the best you can with the training you've had," Harper says. "Because if there are issues, you could be sued, you could lose your job, you could potentially hurt or kill someone accidentally."

The way a dispatcher delivers information to police on how to respond, including the .

In the 2014 police killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, for instance, : that Rice was "probably a juvenile" and that the gun he supposedly had was "probably fake."

How 911 call takers – who talk to the public – and dispatchers – who talk to responders – make decisions in part comes down to training. But training varies widely at the approximately 6,000 call centers in the country.

"Your floor trainer is largely responsible for instilling those habits in terms of how to speak with people, how to interact, how to use your tone of voice, how to stay calm," Orosco says. "Ultimately, we have to make sure that people are on the same page and that's very difficult to do when you have trainers of different tenure and trainers with different experience."

In Denver, the 911 training academy lasts about three months, with an additional three months answering calls alongside a trainer.

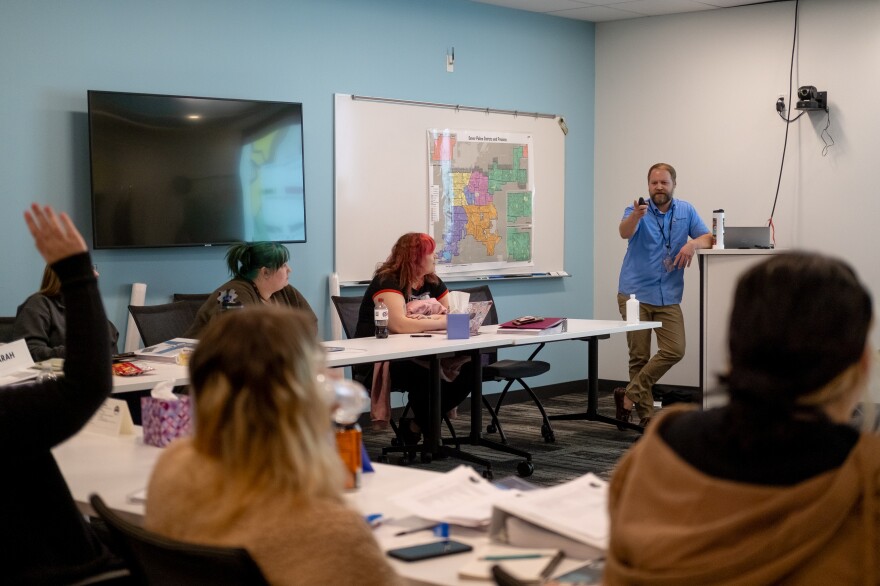

At a recent training, instructor John Shryock taught new hires about the STAR program, which the city rolled out in 2020 as an alternative to police. Every day, eight vans rove the city, each with an emergency medical responder and a mental health clinician on board.

"You're not going to send a cop to fight a fire," Shryock told the class. "Why send a cop to deal with somebody who's in a mental health crisis?"

At the same time, Shryock emphasized the safety of the alternative responders.

"They do not have any body armor. They don't have anything to protect themselves, so one of the concerns that we should have would be ensuring that the scene is safe for them," he said.

Shryock says these types of calls are structured but not scripted. There are particular pieces of data the call taker needs, like where the caller is, where the suspect is, whether there are injuries, when the incident happened and whether there are any weapons.

He instructed trainees to send police if a weapon is present. But even what is considered a weapon isn't always cut and dry. STAR clinicians noted, for instance, that a homeless person carrying a pocket knife shouldn't be considered armed unless they're threatening to use that knife. As a result, 911 changed its policy.

'You take care of the people who take care of the people'

Denver 911 says the majority of the calls it receives are not appropriate for mental health responders alone, even though a most of those calls do not involve violence. Nearly four years after it was launched, the STAR program has responded to just one percent of the city's 911 calls, according to data from Denver 911.

"There are still times where a call that would be perfect for STAR gets a police response instead, or a call that is not appropriate for STAR gets dispatched to one of the vans," Denver 911 Director Andrew Dameron says, "We are working really, really hard so that we are constantly improving."

Dameron says beyond training, another part of improving that process is making sure employees are well supported. Denver 911 increased its starting pay from 20 dollars an hour to 29 dollars an hour. The turnover rate has fallen significantly in the last few years.

"You take care of the people who take care of the people," he says. "If we don't support the folks here, then how can we expect them to show up the way they do for our residents?"

Nationally, there's a push to reclassify 911 professionals as first responders, rather than the clerical classification currently used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Several states have , and in Congress in December.

Advocates say the bill would increase respect for the job and allow for more benefits like mental health support.

"Yes, it's answering phones, but it's so not clerical," says Harper, the former call taker. "We were essentially non-licensed therapists. We were non-licensed medical professionals. We were doing CPR on the phone. That's not a clerical role and it never should have been. And I think that the sooner that happens, the sooner the whole system changes."

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.