Antony Sher met Gregory Doran in 1987 in a Royal Shakespeare Company production of The Merchant of Venice. Sher was performing Shylock, while newcomer Doran had a minor role. The two men have been inseparable ever since. While Doran went on to earn acclaim as a director, Sher’s career as a classical actor had cast him in all the great Shakespearean roles from Richard III to Prospero.

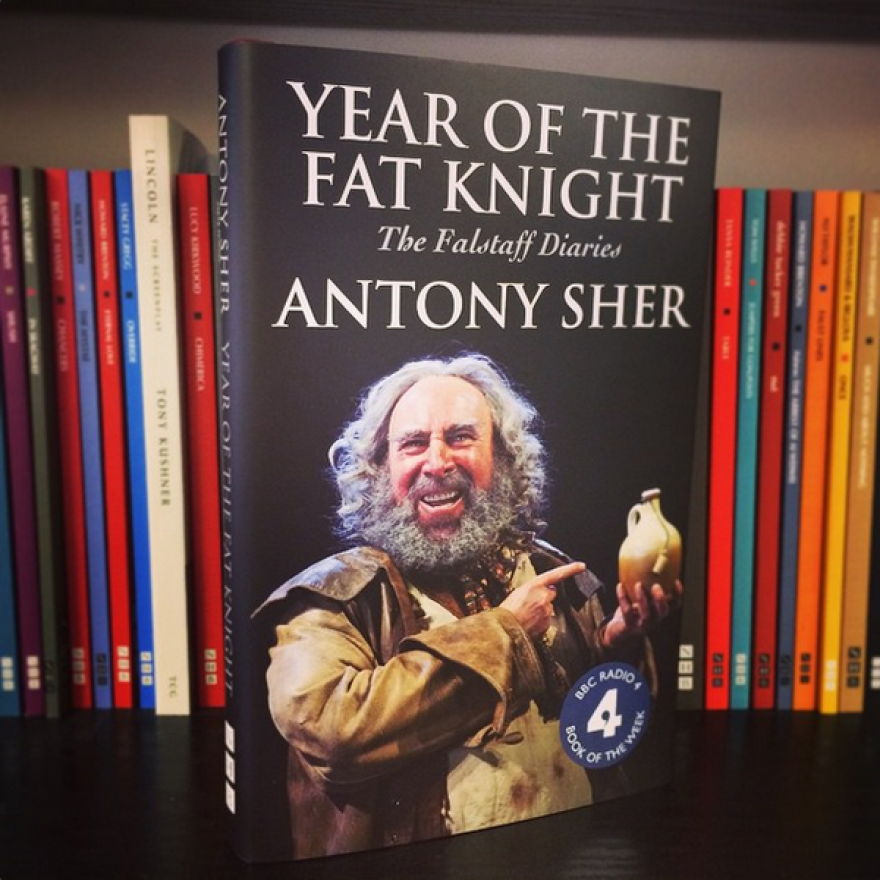

All except Falstaff. In 2012, Doran was appointed to The Job: Artistic Director of the RSC. Eager to produce Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, in the same season, he began scouting the terrain for a Falstaff. He approached Derek Jacobi, who said no. He approached Ian McKellen, who answered with a question: “Why are you looking for Falstaff when you’re living with him?” Doran took the idea home to Sher, who was between runs as a cancer-emaciated Freud in Hysteria. Sher’s incredulous reaction: “Short, Jewish, gay, South African me, as Shakespeare’s gigantically big, rudely hetero, quintessentially English knight?” But he agreed to think about it, and thus began the journey from dithering to determination that Sher chronicles with fascinating, often hilarious candor in his memoir, Year of the Fat Knight: The Falstaff Diaries.

Sher prides himself on being a “character actor,” one who takes his transformative talent to a part, rather than a “personality actor,” who requires the part to come to him. But there was something especially intimidating about Falstaff. Sprawling, noisy, and undisciplined, perhaps he represented Sher’s shadow side, all those qualities that his conscious personality--sensitive, cultured, cerebral--had repressed. In fact, Sher’s preliminary study of Falstaff’s speeches suggested a way into his character: in Part 1, Falstaff vows repeatedly to lay off booze only to deliver a paean to alcohol in Part 2. What if he were played with a serious dependency? Sher himself had recovered from cocaine addiction in his younger years. The contemporary model of substance abuse and denial seemed offer Sher a way to embrace yet maintain a subtle distance from this avatar of the Lord of Misrule. Throughout the long journey of discovery, rehearsal, and performance, Sher keeps returning to the notion that Falstaff can’t simply be “a jolly bloke who likes his drink”; he must be more complex, cast a darker shadow.

The memoir takes us from zero to two-part panorama of epic theatre in thirteen months. While Doran launches into rehearsals for Richard II, Sher has to spend his evenings as Freud again, but protects his mornings for working on Falstaff. (He admits that for an actor in his sixties, learning lines is the monumental feat the public always thinks it is.) He inches along, swinging between a terror of performance and gratitude for the gift of an infinitely layered part. He notes allusions to Falstaff’s noble beginnings—a valuable ring from his grandfather; the possibility that his addiction to sack has eroded an “inbred grandness.” Sher has already decided to give the knight an upper-crusty “plummy accent” when Doran happens to ask, “His voice is going to be posher than yours, isn’t it?” Yes, Sher thinks, posh and pompous yet vulnerable enough to leave room for a fear of damnation.

Then there’s the Fat Suit, getting the belly and the male boobs right, and building the costume over it in a fabric thin enough that the definition doesn’t just disappear into “any old padding.” Sher worries about the toll its weight might take on his back, particularly with additional armor. The real problem turns out to be how profusely it makes him sweat. There he is, working on the whole fat illusion—growing a bushy beard and trimming it short and wide, adding horizontal eyebrows—while the pounds are melting away, threatening to turn him into a Falstaff with gaunt cheekbones.

As rehearsals progress, the timeline shrinks, and the narrative tension rises. For those of us who continue to wonder how all the disparate pieces of a world-class production finally gel in inscrutable symbiosis, Year of the Fat Knight is a riveting read. Like courtroom reporting, it includes Sher’s astonishing sketches of the cast. (The man clearly received an extra share of talent in his DNA.) As we look forward to experiencing the two Henries in close proximity this season at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Sher’s insider perspective on their different worlds also suggests useful questions. Is the first part a “Rolls Royce of a play” followed by Shakespeare “treading water”? Or do we move from a classic structure of heroic action to a vision more Chekhovian?

These are questions I won’t be grappling with myself, at least not publicly, for this is my final essay on Theatre and the Arts for the ŔĎ·ň×Ó´«Ă˝ Journal. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed my run of almost twenty years, and now the time seems right to pass the baton to the impressively qualified and always entertaining Geoff Ridden.

Geoff caught the theatre bug in early childhood performing as a rabbit with a dance troupe in his native England! As an adult, he opted for more gravitas, teaching and writing on theatre at universities in Africa, Europe, and North America. When he moved to Ashland in 2008, he discovered that looking a little like Shakespeare could lead to invitations to impersonate the Bard for OSF. Having had the privilege of acting in a range of Shakespeare plays, he comments “I’ve come to wonder in recent years whether Shylock, Gloucester, and Malvolio have much in common--or whether I myself have only one way of playing older men.”

Molly Tinsley taught literature and creative writing at the U. S. Naval Academy for twenty years. Her latest book is a middle-grade fantasy adventure, Behind the Waterfall (www.fuzepublishing.com)