A non-profit that helps homeless people get back on their feet recently bought a historic hotel, right in the middle of downtown Fort Bragg, on CaliforniaŌĆÖs north coast. It plans to transform the Old Coast Hotel into a transitional housing facility and clinic. But a lot of locals want to resurrect the historic landmark as a tourist destination.

Kevin Scanlon walks out of the main coffee shop in downtown Fort Bragg. One block to the left is the ocean, and miles of trails along the Mendocino coastline. Scanlon turns right, toward the four-block stretch of small shops selling socks, books and tchotchkes.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre a tourist town now. LoggingŌĆÖs done. FishingŌĆÖs done,ŌĆØ says Scanlon, a general contractor who has worked on many of the local buildings. ŌĆ£So weŌĆÖve got to keep the integrity of downtown.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£If you have a lot of transitional people coming, it just turns tourists off,ŌĆØ he says.

Scanlon stops outside the historic Old Coast Hotel. It was vacant for years, until the city approved a grant to the nonprofit Mendocino Coast Hospitality Center to buy it. The agency moved in this summer and began providing case management and mental health services to the homeless. It will eventually use the hotel rooms as transitional housing.

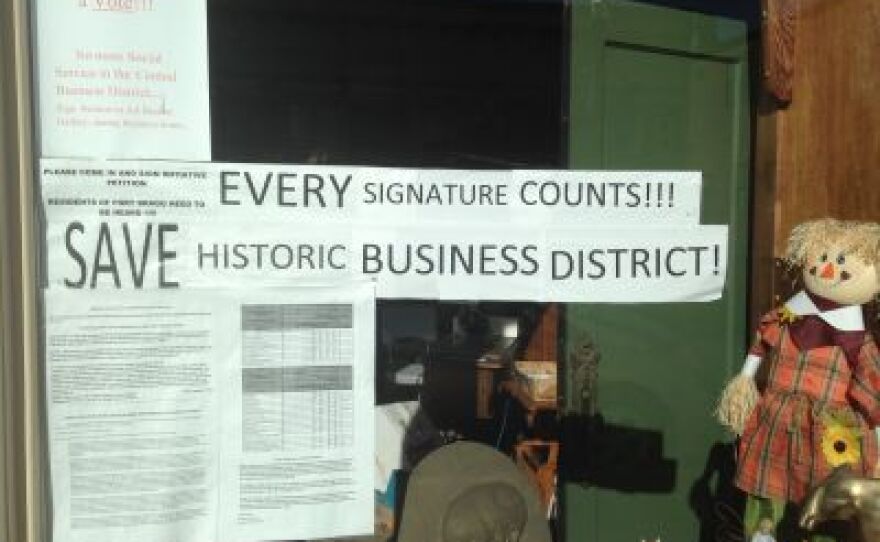

The plans threw the town into an uproar. Scanlon, and more than 1,000 other local residents and business owners, signed a petition to keep the homeless out of the hotel.

ŌĆ£We didnŌĆÖt say weŌĆÖre against it. We said weŌĆÖre against it here,ŌĆØ Scanlon says. ŌĆ£And thatŌĆÖs not being prejudiced, just pragmatic.ŌĆØ

The hotel sits at the gateway to the burgeoning downtown commercial district. Scanlon and other opponents say the building should go to a thriving business. Like a hotel, or a restaurant.

ŌĆ£You could get bed tax. You could get the food tax,ŌĆØ Scanlon says. ŌĆ£That could be a financial gain for the city, as opposed to a financial drain.ŌĆØ

Opponents feel so strongly about the hotel that they filed a lawsuit to block the sale. It failed. They threatened to recall the mayor for supporting the project. That didnŌĆÖt work. Now theyŌĆÖve put that would ban all social services from downtown.

But leaders of the hospitality center say thereŌĆÖs been community pushback at every location they considered.

ŌĆ£Part of it is simply that ŌĆśnot in my backyard,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ says Executive Director Anna Shaw.

But when they landed at the Old Coast Hotel, it really hit a nerve. Shaw says people have nostalgia for watching sports at the polished wood bar, and seeing their teams win. One man proposed to his wife here 20 years ago.

ŌĆ£I think some people have a feeling that itŌĆÖs kind of too good for the homeless and the mentally ill,ŌĆØ Shaw says.

The building is more than 100 years old and is considered an architectural gem. The hallway walls are pressed tin. The hotel rooms upstairs still have Victorian details ŌĆö layered window dressings, wainscoting, marble fireplaces.

Shaw says that when homeless people have a nice place to stay like this, they do better.

ŌĆ£Because peopleŌĆÖs self-esteem is higher. ItŌĆÖs much harder to throw trash on the floor when the room looks beautiful like this,ŌĆØ Shaw says. ŌĆ£If itŌĆÖs really squalid, thereŌĆÖs no incentive to behave.ŌĆØ

She says being downtown is also important. ItŌĆÖs easier for people to get to appointments, and it helps reduce stigma when people are integrated into the community.

ŌĆ£Lots of homeless people and people impaired with mental illness feel marginalized,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs important that folk get to come to a place where the value we place on them is expressed through the building.ŌĆØ

But Anne Marie Cesario, a retired social worker, says thatŌĆÖs not the way to combat stigma.

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs like using people as guinea pigs in order to further some liberalŌĆÖs idea about consciousness raising,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs inappropriate.ŌĆØ

Cesario is one of several mental health professionals opposed to the downtown location. She says itŌĆÖs not private enough, especially for people who suffer from paranoia.

ŌĆ£They donŌĆÖt want to be seen when they go to the doctor. They donŌĆÖt want to be seen when they go to the therapist,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£That building is on one of the busiest corners in town, and itŌĆÖs a four-way stop.ŌĆØ

She, and other members of the Concerned Citizens of Fort Bragg, believe a more appropriate location would be the former social services building on the edge of town, near the hospital and police station. Or an old motel on Highway 1. Or a building 3 miles north of Fort Bragg.

The Hospitality Center declined all those properties. And now the Concerned Citizens group is hoping voters will pass their ballot measure prohibiting social services in the downtown commercial district, retroactive to Jan. 1, 2015.

But even if the measure does pass, itŌĆÖs unclear what impact it will have on the Old Coast Hotel. An analysis from the city attorneyŌĆÖs office says that, under legal precedents, the Hospitality Center would most likely be allowed to continue operating at the hotel. It would be grandfathered in under any new zoning rules as a ŌĆ£non-conforming use.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£This will result in nothing but lawsuits,ŌĆØ says Scott Menzies, who runs a tai chi studio in town, and helped organize another group of small business owners, called Go Fort Bragg, who are against the ballot measure.

ŌĆ£The measure is so broad-reaching, it will cause far more collateral damage,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖre using a cannon that targets every other social services organization in the business district.ŌĆØ

All the tension and fighting is frustrating for Debbie Gibney, a client of the Hospitality Center.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm bipolar and I have post-traumatic stress syndrome, from being an abused wife,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£I take medication and I see a therapist regularly.ŌĆØ

Gibney is 58. A few years ago, she was forced to retire early from her job. Then she lost her home. She got help at the Hospitality Center, and now sheŌĆÖs back on her feet, helping other homeless people at the Old Coast Hotel.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm proud to walk in here,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£Because of the beauty of the building, and the reception that we get here, and the way the staff accepts us and loves us unconditionally.ŌĆØ

At the agencyŌĆÖs previous location, in a strip mall near the DMV, clients had to wait in an alleyway for appointments. But since moving to the Old Coast Hotel, Gibney notices the clients are more relaxed and more respectful.

ŌĆ£We feel like weŌĆÖre part of the city now,ŌĆØ she says.

Copyright 2015 KQED